FRI, JUNE 09 2023-theGBJournal |During his inaugural address on Monday 29 May President Bola Ahmed Tinubu announced the end of Nigeria’s fuel subsidy.

Phasing out fuel subsidy was a manifesto pledge and the decision to implement it may have been brought forward by the absence of any provision for fuel subsidy in the current government budget beyond June. (The current budget was bequeathed by the previous administration.) Subsidies for petroleum (also known as Premium Motor Spirit, PMS) are believed to have cost the government in the region of US$9.0bn last year.

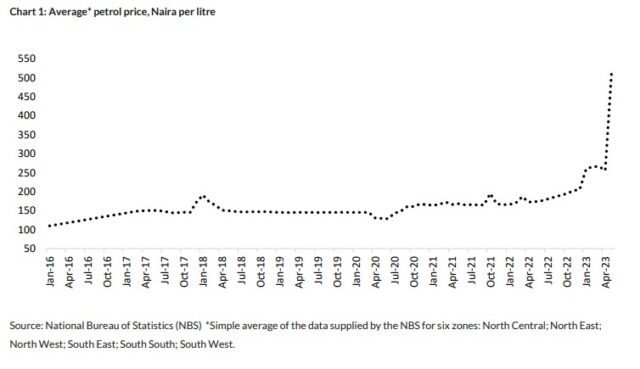

According to data released by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) the price of petroleum in Lagos, for example, rose from N184/litre (40 US$ cents at the official exchange rate) on 29 May to N488/litre (US$1.05) on 31 May, a rise of 165%. We will return to the subject of exchange rates later in this report.

As one would expect, there were long queues outside petrol stations in Lagos on Tuesday 30 May. Traffic was light over the following two days but built up again over the weekend, a testament to the inelasticity of demand for fuel.

The NNPC still stipulates prices at which its stations sell petrol, and clearly these prices will influence private-sector petroleum marketers. It seems that the NNPC’s published prices truly reflect input costs, and therefore can be considered market prices.

Differences between published NNPC prices for different regions are small and reflect transport costs (e.g. the price is 11% more expensive in Sokoto in northern Nigeria than in Lagos). We consider petrol prices effectively deregulated.

Clearly, there are multiple knock-on effects – and many opportunities – stemming from fuel subsidy removal. We will look at public finances, inflation, the consumer, companies, and the stock market.

Before we do this, however, we need to consider how significant fuel subsidy removal is in the context of Nigeria’s international standing.

An historic step

Over several decades, Nigeria’s multilateral partners, with a high degree of consistency, have called for three key reforms: removal of fuel subsidy; unification of foreign exchange rates, if not an actual free float of the currency (unification of foreign exchange rates was also mentioned during the President’s inaugural address); effective power sector reform (ditto).

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB) and a host of development agencies and donor nations over the years have made these demands, which have gone unheeded (for the most part). Now one of these key reforms has been passed. It is an historic step.

This administration has pushed ahead where previous administrations have either not attempted to reform the fuel subsidy or begun to reform it and then backtracked in the face of opposition. There is no shortage of calls in Nigeria today to mediate, negotiate and generally water down what the President has decreed, but there is no sign that the Federal Government is going to reverse its decision.

Public finances and eurobonds

The first beneficiary of fuel subsidy removal is the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN). In 2022 the FGN’s budget for fuel subsidy was N4.0 trillion (US$8.6bn), which represented 22.1% of its total budget of N18.1 trillion (US$39.0bn). The subsidy swallowed up 40.1% of budgeted aggregate FGN revenues of N9.97 trillion.

Doing away with fuel subsidy clearly has positive implications for Nigeria’s fiscal deficit, which was budgeted at N8.17 trillion (US$17.6bn) in 2022. The government-owned NNPC’s purchases of petroleum products take the form of swaps, of the NNPC’s crude oil for imported products, with petroleum (until 31 May) sold at subsidised Naira prices.

Given the nature of the swaps, it seems that the NNPC is saving itself the equivalent barrels of oil, with the value accruing to the government (its shareholder). Removing fuel subsidy is therefore a US dollar saving for the FGN.

International bond markets have been quick to spot this, with yields of FGN US dollar Eurobonds tightening across the curve immediately after the announcement. The average yield of six traded FGN Eurobonds fell from 11.7% immediately before the announcement to 11.0% at the end of last week. (An international rally in bonds, following the resolution of the US debt ceiling issue, was also a contributory factor.) Even then, this does not seem like excessive optimism to us, and we continue to believe that FGN US dollar Eurobonds represent good value.

An incentive to refine

Consider the case of an integrated oil producer and refiner in Nigeria. When it extracts oil and sells it, it earns US dollars.

When it diverts its own production for refining it makes products for domestic consumption priced in Naira. Until 31 May the price of the petroleum component of those products was regulated and far below the free market price. This was a disincentive to refine. The disincentive has now been removed.

The same was true of refiners, unless they were compensated with subsidies to bridge the gap between the true cost of their products (i.e. crude oil plus all refining costs plus finance costs) and the subsidised petroleum price. The removal of subsidies provides an incentive to refine.

Investors have also marked up the prices of mid and downstream oil companies, reasoning that, in the absence of the rigid pricing formula that accompanied the subsidised price, it will be possible to improve retail margins.

Implications for listed companies

The stock market was enthused by the announcement of fuel subsidy removal, with the NGX All-Share Index gaining 5.23% the day after it was announced. Since then, the market has been more circumspect with barely any further gain in the index overall. We believe the market is beginning to assess the broad based costs of fuel subsidy removal to listed companies.

It is often said that the fuel subsidy is a subsidy for the wealthy, in particular those who drive cars. This ignores the fact that many domestic generators are fueled with petrol rather than diesel, in particular small domestic generators in widespread domestic and commercial use. Transport costs are not only borne by those who drive cars but by users of buses, taxis and okada motobike taxis. Transport costs are reflected in the costs of fresh food, packaged food, and almost all other goods. It is fair to say that fuel price removal is an inflationary shock for everyone.

Ultimately, these costs will be borne by companies across the board, whether in the form of increases in direct costs or in response to demands for salary increases. One way or another, fuel price rises will work their way into the cost base. It is unlikely that companies will respond with immediate salary increases so we expect the consumer to be hit in pocket. After the disruption caused by cash shortages early this year, the first half of 2023 is a tough one for the Nigerian consumer.

Choose industries with inelastic demand

Given that the consumer will be under pressure, we have reservations about companies that benefit from discretionary spending. Brewers and some consumer product companies may face challenges. Companies that may continue to perform well are those whose products enjoy inelastic demand, notably telecom companies and banks. We will explore these themes in future publications.

Note that there are, at this stage, limited implications for fixed income investments arising from fuel subsidy removal.

A fully liberalised fuel price

One of the assumptions in this report is that fuel prices are now full liberalised, i.e. that they reflect market prices, including a market price for wholesale fuel and a market price for foreign exchange. We can check this assumption using a Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) pricing template and see how it applies to the prices announced by the NNPC for 31 May.

The two principal variables in the pricing template are European wholesale petroleum prices and the Naira/US dollar exchange rate. Since we know the European wholesale petroleum price (available from Bloomberg, among other sources) we can derive – we have to say approximately – the implied Naira/US dollar exchange rate.

Note that fuel subsidy was not a cash payment: rather it represented an opportunity cost (recorded in the annual government budget) of what would have been realised on behalf of the Federal Government of Nigeria if the country had not entered into swaps (of barrels of oil) for imported petroleum products.

That budgeted cost had an implied exchange rate attached to it which was the official exchange rate, or the I&E Window rate. The question is what the implied exchange rate is now.

A necessary caveat when using this method is that information is scarce and is not up to date, therefore we have used several bold assumptions to update it ourselves.

Nevertheless, we are satisfied that our assumptions are reasonable and that the exchange rate implied by newly-announced petroleum prices is much closer to the parallel market rate (which, according to various sources is around N750/US$1) than the I&E Window rate (of around N465/US$1).

Risks

As the government of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu is in the process of being formed (following general elections in February and March this year) key fiscal and monetary policies cannot be described with any certainty. While the manifesto of the All Progressives Congress (APC) contains clear policies, it is not known which policies will be prioritised nor when they will be implemented. At the time of going to press key ministerial appointments have yet to be made.

The removal of fuel subsidy is an APC manifesto pledge and was announced by the President during his inaugural address on 29 May, immediately followed by re-pricing of petroleum prices (or Premium Motor Spirit, PMS) by the NNPC. Readers should be aware that previous attempts to reform the fuel subsidy, several years ago, were reversed. There is no guarantee that the current policy will not be reversed or amended.

This report discusses what we consider to be the likely effects of fuel subsidy removal, but only in isolation. We are unable to assess the effects of fuel subsidy removal in the context of other fiscal and monetary policies.

These policies, yet to be announced and implemented, may have a significant effect on the possible outcomes described in this report. For example, one cannot rule out the creation of a stabilisation fund designed to cushion consumers from the effects of fuel subsidy removal, but how such a stablisation fund (if any) would be funded is an open question.-A Coronation Research Report

Twitter-@theGBJournal|Facebook-the Government and Business Journal|email:gbj@govbusinessjournal.com| govandbusinessj@gmail.com