…Today few mainstream emerging markets run deficits and nearly all have hefty FX reserves

…If we assume the US dollar will weaken in the coming decade, this implies that upping exposure to EM and FM now will give investors the best relative valuations since 2003 (using the equity chart as a proxy).

By Charlie Robertson

FRI, NOV 03 2023-theGBJournal| While much has been written about the US dollar’s demise, that’s not the focus of this month’s Themes from FIM.

It took 30 years, including a Great Depression and two World Wars before a bankrupt British Pound definitively lost its hegemonic role to the biggest economy in the world.

So even if China was bigger than the US today (instead, the US at $27 trillion GDP is 50% bigger than China’s $18 trillion), the US dollar would rule until at least 2050.

That in turn means we have at least another 30 years in which emerging market returns will be governed by the US dollar’s ups and downs.

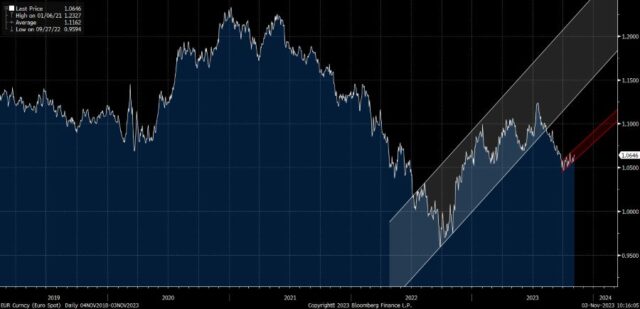

Just one (complicated) chart

Here we show the US dollar in grey, on the right-hand scale where weak is up and strong is down. We compare it to the relative valuations of Emerging Markets to Developed markets.

When the red line is high, it means investors love emerging markets. When it’s low, they prefer developed markets. There are 3 conclusions., outlined below.

On EM, MENA, improving fundamentals and Frontier

Firstly, the message here is that emerging markets do poorly when the US dollar is strong and vice-versa.

Why does the currency matter? Weakening emerging market currencies means external debt ratios get worse, credit ratings suffer and that leads to a vicious circle.

The opposite applies too. Stronger emerging currencies cut domestic inflation and allow interest rates to fall which encourages credit growth and faster GDP growth, which attracts more capital, and together this drives up credit ratings, which reduces borrowing costs, and we have a virtuous circle.

The only group of countries which may be immune to the worst of these ups and downs are the Gulf countries with US dollar pegs. When the US dollar weakens, they tend to benefit from higher energy prices.

When the US dollar strengthens, they are among the few markets that don’t suffer relative to the US, and they tend to have the FX reserves to help smooth out the hit from lower energy prices.

Counter-intuitively, investors in 2010 should have reduced EM exposure just after China’s stimulus helped pull the world economy out of recession, and should have invested heavily in the main instigator of the global financial crisis, the US.

In 2000, they should have sold the US when it was discovering tech, and bought EM after Asia’s currency crisis of 1997 had already brought down Russia and was about to topple Argentina into default.

Given this history, it is not hard to imagine that our excitement about US tech (again), and concern at Argentina’s likely default (again) is sending us a strong message.

Second, the low for EM relative to DM seems to be on an upward slope, ie we don’t need to see EM sell off as much as in the past. This is because EM is changing for the better.

For example, gross enrolment at secondary school in Mexico (which triggered the Latin American debt crisis) has risen from 44% in 1980 to 98% in 2021, according to the World Bank.

The current account deficits that triggered the 1997 Asian crisis had mostly disappeared by 2013. Only a Fragile 5 emerging markets were targeted during the Taper Tantrum. Today few mainstream emerging markets run deficits and nearly all have hefty FX reserves.

Third, Frontier markets (FM) like most in Africa are the extreme in this relationship. The “Doomed Continent” of 2000 became the “Africa Rising” story of 2012 on Economist magazine front covers, as the US dollar went from overvalued to undervalued.

Today with a strong US dollar once again, it is no surprise that Ghana, Ethiopia and Zambia should all be restructuring their debt, much like Latin America in the 1980s.

If we assume the US dollar will weaken in the coming decade, this implies that upping exposure to EM and FM now will give investors the best relative valuations since 2003 (using the equity chart as a proxy).

Investing exactly at the bottom of the market

Timing the exact bottom of a market is hard. However, the opportunity of buying cheaply and selling high is an attractive strategy, available now to global asset allocators.

Investors can sell DM equities when the US represents an ahistoric 60-70% of global market capitalisation, and use those strong dollars to buy cheap EM assets – a strategy to be revisited in 2030 when we expect the EM markets space to be relatively expensive and DM assets to be cheap.

Recent market moves

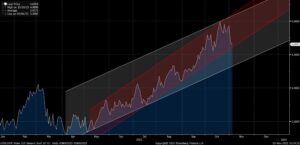

It would be a lovely surprise if this Themes piece has come out at the same time as the $ is about to begin a 10 year sell-off.

The relative dovish Fed this week has helped the EUR sustain a month-long strengthening trend (red lines). But having seen one trend line of EUR strength fail in mid-2023 (the white lines), we can’t be sure.

This week I suggested the Vietnamese dong (VND) would weaken to 25,500/$ in 2024 but if the JPY and Chinese Yuan (CNY) stabilise or strengthen due to $ weakness, maybe the VND can stabilise where it is.

On US 10 year yields, the last week is helpful for EM and Frontier debt. But we’re not yet out of the rising yield channels since 2Q, not even the steeper red one since the end of August. Like the Fed says .. we’re all data dependent.

CONCLUSION

We know EM assets are cheap, and I’m sure investors in the space will do well over the long-term.

But I can only cross my fingers that this week is the turning point. We don’t have the oversold crash feel of the mid-1980s or late 1990s in EM – but after 10 years of misery, maybe we don’t need it.

Charlie Robertson is Head of Macro Strategy, FIM Partners UK Ltd

X-@theGBJournal|Facebook-the Government and Business Journal|email:gbj@govbusinessjournal.com| govandbusinessj@gmail.com