By Charles Robertson

MON 14 MARCH, 2022-theGBJournal| This piece focuses on how net exports are impacted in Africa, and how for many this has not been well reflected in the debt and currency markets since 23 February.

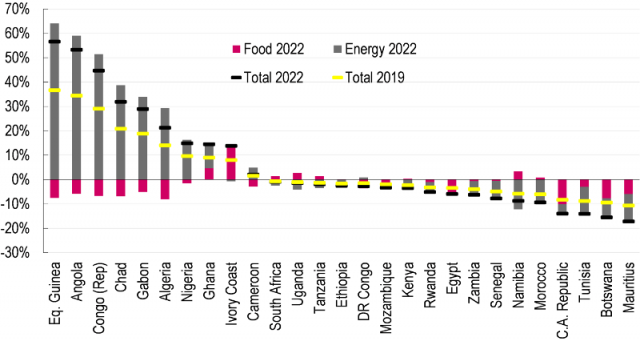

The biggest beneficiaries of commodity price changes are unsurprisingly the oil exporters, from Equatorial Guinea to Algeria, with the benefits far outweighing the cost of higher food imports. It is interesting to see Chad in this group, given it joined with Ethiopia and Zambia a year ago in seeking a G-20 debt restructuring agreement.

The net export benefit to Nigeria needs to be considered alongside the negative fiscal impact from the re-introduced fuel price subsidy. But if we see oil average $110/bbl this year, GDP growth could be 5.5% and we think the naira would end the year at NGN430/$.

For Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire – we need to recognise that cocoa has not jumped in price like the broader food category has. So our chart is misleading, and Cote d’Ivoire looks more like SA than Nigeria. Ghana benefits but again its cocoa exports are not rising, so it benefits less than Nigeria, but gets a lift from gold.

When we compare this to the shift in Eurobond prices and currencies since 23 February, some significant discrepancies emerge.

The only significant market beneficiary has been Angola where the 2029 Eurobond price had risen 2% and the currency was 6% stronger. Meanwhile less liquid Republic of Congo, which nearly has the same exposure as Angola in terms of net exports, is down about 2% on both (the currency is euro-linked). Note on Angola, we suspect this upward bond is too small. Nominal GDP is going to jump, and its debt ratios should improve significantly with this higher oil price.

What’s harder to explain are the bigger falls, particularly Kenya whose 2032 Eurobond when we started writing this yesterday was down 10% while yesterday there had also been an 11% fall in the Egypt 2033 Eurobond. The market rallied back well over the last 24 hours, but it is still odd that Egypt and Kenya are two of the three worst hit credits.

Below we try to outline some macro factors that may be at work. But our conclusion is that price moves are related to market positioning or misperception, not underlying economic drivers.

Liquidity is probably a significant factor. Egypt and Cote d’Ivoire have large liquid bonds and in a flight to safety, it is unsurprising they sold off. Egypt is not a net beneficiary of commodity price moves, and will take a hit on tourism, so should sell off more than Cote d’Ivoire. But Egypt should not, in our view, be the worst performer among African credits. As mentioned on 7 March, long-dated dollar bonds in Egypt were the first non-safe asset we thought we were worth buying this month.

Recent balance of payments figures offer some support for our view, with the energy balance in surplus in 3Q21. We think natural gas is included in the oil and oil product rows in the tables above (a detailed look at 3Q21 figures show the energy balance including natural gas is identical to the table cited above), but might be missed by sell-side research which focuses only on oil.

Wheat and maize imports will increase in price by a few billion dollars if prices stay elevated, and we suspect the bread subsidy will rise from nearly $3bn in the 2021/22 budget to $4-5bn in calendar year 2022. Suez Canal receipts may pick up as higher shipping fuel costs discourage the Cape route for Asia/Europe trade. Tourism receipts though will be hit as we pointed out in our FEM note on Tuesday (link above).

Egypt would look riskier in the short-term if the currency was allowed to weaken (as the external debt to GDP ratio would worsen), but we suspect the Central Bank of Egypt would prefer to keep the currency stable at this uncertain time. Our Cairo based analyst Ahmed Hafez thinks foreign exchange reserves are sufficient to weather the outflows we are seeing at present. I agree. In the medium-term the currency is 15-20% overvalued so should depreciate, but the inflation differential with the US currently is not yet worsening that figure.

Tunisia ought to be the worst market performer, given it has the worst macro-hit of any country whose Eurobonds we follow. Fundamentals are also shaky. However, we think market positioning in this credit is lighter. In addition, an IMF deal might be coming which would improve investor confidence a great deal. Just a few months ago we were targeting a Eurobond price of 85-90 if the IMF deal came through.

Kenya’s economy ought to barely affected, given our chart above, but its 2032 Eurobond was down 10% in price yesterday. The relative recovery in the last 24 hours is justified.

In the medium to long-term Senegal and Mozambique and now Namibia are winners from the LNG and energy angle – but admittedly that doesn’t help their creditworthiness today. Other LNG winners in the short-term are Egypt, Algeria and Nigeria, as our analyst wrote earlier this week.

Ghana is also interesting here, with a 5% hit on the Eurobond (7% yesterday) and currency, despite benefiting from higher energy prices.

Inflation and subsidy costs

It’s possible that higher inflation is a factor impacting on investor perception of African credits. Yvonne Mhango’s report showed that food represents a third to a half of CPI basket in key economies we follow (about 17% in SA). But moves in bond prices don’t look consistent with that issue.

Subsidy costs could be another factor. As Yvonne noted, there are subsidies on fuel in Nigeria and Kenya. In Egypt there are also subsidies for small loaves of bread. But again, the bond moves don’t look consistent with this.

The tax and debt vulnerability problem

One big problem relates to taxes. My last report of 2021 was about how vital tax rises in Africa would be in 2022 (and beyond) if countries were to remain credit worthy. Ghana’s public debt to tax revenues ratio at over 600% in 2021 highlighted how important the controversial e-levy tax rise was in the 2022 budget. We also pointed out Egypt’s very high interest payment to revenues ratio which does make it vulnerable.

Now consumers across Africa are likely to be hit by fuel or food price rises, or in some cases both. Our telecoms analyst remembers that in Nigeria in 2007 when global food prices were surging, customers stopped buying beer so they could carry on using their phone (I suspect our consumer analyst remembers them stopping using their phone so they could carry on buying beer). He asked whether tax rises might have to be reversed in 2022, particularly in countries facing elections, in August in Kenya and end-February 2023 in Nigeria.

Unfortunately, governments have little choice. Any fiscal room that governments had in the face of the COVID hit in 2020, is much reduced now.

We suspect the IMF and other creditors will be understanding about the pressures hitting governments now. But it is fair to argue that most African sovereigns have taken another blow from this global commodity price shock. Some price weakness is warranted for most.

Conclusion:

We do not think market moves in African Eurobond pricing is explained by their net export exposure to energy and food prices. We think market positioning before 23 February was more important. We do think this commodity shock hurts most African sovereigns, so some weakness for non-energy exporters is justified. But we do NOT think Kenya and Egypt should be among the hardest hit, and some recovery in Egypt’s dollar bonds is justified.

Ghana is a harder call, as it should benefit from higher commodity prices, but is a particularly indebted economy. We think the bigger hit warranted by fundamentals was in Namibia and Tunisia. Lastly, we suspect Angola’s Eurobonds should be better bid than they have been, given the improvement likely in their debt metrics.

Charles Robertson is Global Chief Economist Renaissance Capital

Twitter-@theGBJournal|Facebook-The Government and Business Journal|email: gbj@govbusinessjournal.ng|govandbusinessj@gmail.com