…Banks become flush with cash, like Morocco where bank lending is closer to 100% of GDP than the 20% of GDP in Nigeria.

By Charlie Robertson

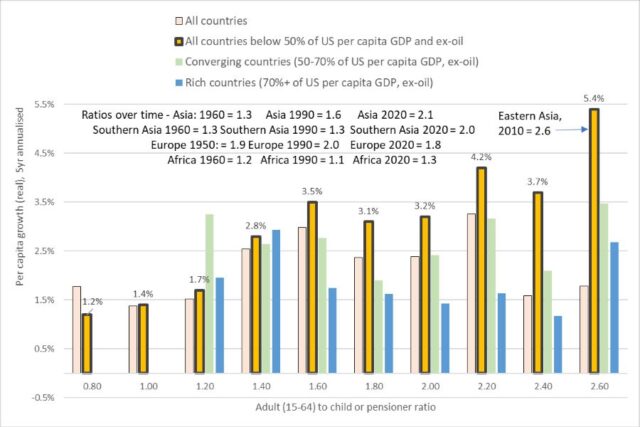

THUR, JULY 13 2023-theGBJournal |This might be the most important chart you’ve never seen. It’s the first in what will be a series of Themes From FIM.

We’ll explain how we see the world, how to make the best possible investment returns from these views and provide ideas worth at least 5 minutes of scintillating conversation with your family over the dinner table. Do let me know how that goes.

Is it good to be young? Most of us reminisce about our youth, but for countries the answer is no. What we found when looking at economic growth in every country since 1960 is that the youngest countries record the slowest per capita GDP growth.

Among the Frontier and Emerging Markets (FEM) that FIM focuses on, most have per capita GDP under half that of the US (the yellow columns in the graph above), and the youngest countries have just 1 adult per child or pensioner (the bottom axis). Their per capita growth is just 1.4% per annum. Why?

If half your population are children (or pensioners), they are not doing productive work in factories or offices. Hopefully they’re at school but they’re adding nothing to GDP. One of their parents may be at home looking after the large family.

The odds are that none of them are earning much money, so they are not putting savings into the bank. Niger is the youngest country in the world with a median age of 15 years old, and how many wealthy 15 year-olds do you know? Of course they’re not paying much in the way of taxes.

There is a huge need for jobs for the children as they become adults, and infrastructure (from schools to electricity to transport) to support them. But there’s little cash to pay for it, either in the banking system or the government treasury.

This changes dramatically when countries get older. By the time the ratio of adults to dependents rises from 1 to 2, per capita GDP growth more than doubles to 3%, and at 2.5 adults per kid or pensioner, per capita GDP rises by a fantastic 4-5% per annum. By this point, 2/3 or more of the population are working age.

They do get jobs, earn and save money, and pay taxes. Banks become flush with cash, like Morocco where bank lending is closer to 100% of GDP than the 20% of GDP in Nigeria.

Interest rates fall due to the rise in savings. Investment picks up. We have more people working, and more savings to help create jobs, and more tax revenues so the government can provide the infrastructure to drive fast growth.

Hello Vietnam (2.2 adults), the Philippines (1.8 and rising), Bangladesh, Indonesia and that consensus EM overweight India (2.1 adults for each). Default risks fall and credit ratings rise.

And yes, while one year of strong GDP growth is usually priced into equity markets, decades of high growth due to the double demographic dividend does give you very good returns. It’s why we love these markets.

The Gulf countries look particularly good on this metric, with Saudi Arabia’s ratio now at 2.5 adults in 2020, up from 2.1 in 2010 and 1.4 in 2000, while the UAE is off the charts at 5.2. Migrant labour helps boost their growth rates. Our MENA equities fund is overweight in both.

The only caveat is that while the structural boom case exists for both, volatile oil does distort the growth picture, which helps explains OPEC+ efforts to suppress oil price volatility.

Markets find it easy to price these markets highly once the high growth is obvious – just see India today. They struggle more when countries have only recently begun the take-off; there is still scepticism that Bangladesh will be as successful as we expect.

And markets are really bad at identifying the countries about to take off, like Egypt and Pakistan, but they will be the surprise winners of coming decades. More on them in future Themes from FIM.

In the West, the media’s focus is more on a worsening ratio of adults to dependents, not because of too many children, but because of too many pensioners. We don’t have the historical evidence to be sure how that will play out in terms of GDP growth, but few expect old societies to be growing fast. Fortunately at FIM, old countries are not our focus.

FIM uses this data to guide us on long-term growth for equity markets and to guide us on default risk in debt markets. But we cannot ignore exciting opportunities that can be provided by the economic cycle and a new pro-reform climate. While Nigeria (median age 16, with 1.2 adults per dependent) is too young for a multi-decade high growth boom, the new president is on course to deliver medium-term outperformance we can try and capture too.

No single graph answers all the questions an investor should have, but demographics does provide a tried and tested template that we hope gives us an edge over markets that focus so much on the short-term.

Charlie Robertson, Head of Macro Research at FIM Partners.

For further information, please contact:

Charlie Robertson, Head of Macro Research, +44 (0) 7747 118756, crobertson@fimpartners.com

Raya Majdalani, Investor Relations and Communications, +971 4 426 7681, rmajdalani@fimpartners.com

Twitter-@theGBJournal|Facebook-the Government and Business Journal|email:gbj@govbusinessjournal.com| govandbusinessj@gmail.com