…The Naira Fixed Income Rate Puzzle

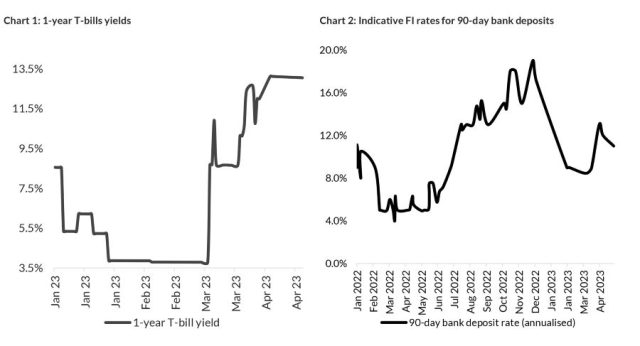

TUES, MAY. 02 2023-theGBJournal|2023, so far, has been an exceptionally volatile year for Naira-denominated savers, with 1-year T-bill rates oscillating between 3.78% and 13.05% while Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) bond rates have been more stable.

To make things more complicated, 90-day deposit rates available to financial institutions (rates which they can pass onto their customers) have varied between 4.00% and 19.00%.

The question, this year, has been not how to position a Naira fixed-income portfolio, i.e. whether to take short-dated T-bills or long-dated bonds, but when to buy high-yielding T-bill and short-term deposits.

Complacent fund managers, who were not aware of the dynamics of the market and who locked in money at low rates, had a rude awakening by the end of Q1 and appear to have been confused by events.

How does a canny investor make the best returns in these conditions? Note that average FGN bond rates have, for the most part, been higher than 1-year T-bill rates and 90-day deposit rates, so certain kinds of investor would have been happy with FGN bonds, and could have accessed them by buying Fixed Income mutual funds.

But many investors either have a short time horizon or like to see their cash redeemed on a regular basis, and the key for them has been how to maximize returns on short-term fixed-income investments.

As all investors know, conditions were far from normal at the beginning of 2023. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) was in the process of withdrawing old banknotes from the system and replacing them with new ones.

Such changeovers are very rare, and the prospect of millions of Nigerians depositing a trillion or more old Naira banknotes with their banks was going to create unusual conditions, in this case, a surfeit of bank liquidity.

And, as anyone who studies short-term movements in short-term rates knows, a surfeit in liquidity usually results in a fall in T-bill rates. Banks, engorged with their clients’ money in current accounts, were big bidders at the CBN’s T-bill auctions and rates fell during January, sustaining low levels during February and the early weeks of March. These were bad times to lock in a short-term investment.

If it was not clear that conditions were abnormal, then one only had to look at what was happening on the street. First, there was a shortage of cash as people took their banknotes to deposit with banks. At one point many shops stopped taking cash, fearful they would not have time to deposit it.

Then long queues formed at ATMs, as people relying on cash waited, often for hours and sometime overnight, to get hold of precious new-issue banknotes. As the interbank system processed a high number of electronic transactions it began to show the strain, with people reporting multiple problems with card payments and electronic transfers.

Next, and following a judgment from the Supreme Court that ruled against the banknote replacement policy, the CBN instructed commercial banks to reissue the old banknotes. The queues at ATMs disappeared within a fortnight, and banks were faced with the task of emptying out customers’ current accounts and issuing them with banknotes again.

Banks became much less liquid than they had been a few weeks earlier. This, not surprisingly, made them weak bidders at the T-bill auctions, systemic liquidity was lower than before, and 1-year T-bill rates shot back up in March.

The CBN and the DMO

What of the government? Surely, during an observable surge in system-wide liquidity, this was a good time to front load the year’s scheduled debt issues? The liquidity was there for the taking and all the government had to do was to increase the size of its auctions.

Here it becomes a little complicated and a canny investor would have done well to have taken professional advice. The key point is that there are two agencies through which the government issues debt: the CBN, which auctions T-bills, and the Debt Management Office, which issues FGN bonds.

The DMO and the CBN have been taking different approaches, year-to-date. The DMO has reacted to the enormous level of bids at its regular auctions, particularly during February and March, to issue more FGN bonds than scheduled. Allocation levels have been raised to reflect the volumes actually bid by investors and have exceeded the amounts originally offered.

This is the explanation why FGN bond rates have not moved very much this year, with our average calculation of FGN bond rates in the secondary market varying between 12.68% and 13.85%.

The CBN has been conducting T-bill auctions somewhat differently. Although it has elevated allocation levels a little bit, it has generally not done this to the extent that the DMO has. In fact, as the chart shows, it has tended to allocate T-bills in amounts quite close to those initially scheduled. Not surprisingly, when a large volume of bids meets a small allocation, the discount rate and the implied interest rate fall.

This explains why 1-year T-bill rates fell so precipitously during January and kept low during February and the early part of March, reaching as low as 3.78% per annum.

The reversal of the CBN’s policy in March reversed the direction of 1-year T-bill rates, which surged to 12.63%. Managing short-term Naira liquidity really was a matter of figuring out the best time to make the move.

The redemption schedule of FGN bonds was also a major factor, which was also visible, and we will discuss this a little later.

What of the bank themselves?

So far, we have discussed the overall liquidity of the financial system as very much the same as the liquidity of the banks. It is not always correct to assume this (there is the considerable liquidity – some N15.0 trillion – held by pension funds, largely in government securities), but during the first part of 2023, this has proven to be a helpful assumption because so much was happening to banks’ liquidity, one way or another.

Banks transmit liquidity pressures in the financial system very effectively these days because of their own liquidity issues.

Last September the percentage of depositors’ funds that they are required to deposit with the CBN, the so-called Cash Reserve Requirement (CRR), was raised from 27.5% to 32.5%, with some banks stating that their effective rates are higher than this. This makes banks scramble for customers’ deposits, from time to time, when liquidity conditions are tight.

This has given a different twist to making short-term investments in Naira. T-bill rates rise and fall, but so do the deposit rates offered by banks to financial institutions, namely institutions that themselves are able to collect and pool large sums of investors’ cash.

A fund management company with several billion Naira of investors’ money to invest is of interest to a cashstrapped bank, or at least this was often the case in 2022 and continues to be the case, sometimes, in 2023. As with the art of investing in T-bills this year, timing counts for a lot.

(Note that is not a permanent feature of the Nigerian banking system, nor a feature of banks generally. The situation is brought about by the high CRR level and the fact that other drivers of liquidity, notably the reversal of the banknote withdrawal policy, put pressure on banks to balance their books – at the margin, because we are by no means talking about all their deposits – by offering high deposit rates rather than drawing on the standing lending facility of the CBN.)

Redemptions and Auctions

What of other drivers of market liquidity? In a normal year (and 2023 is proving to be far from normal) it makes sense to forecast market interest rates by making an estimate of the government’s budget deficit and then figuring out how the CBN and the DMO are going to fund it, i.e. what level of overall debt issuance is required. A high level of Naira funding is likely to drive up interest rates.

Our overall view is that T-bill rates and FGN bond rates are set to rise over the course of the year as the Federal Government seeks to finance its considerable deficit via the Naira bond markets (while US dollar Eurobond rates are so high that it makes little sense to finance in the international markets, though some multi-lateral loans may be available during the course of the year).

Caveat

This overall view served us well in 2022, though we need to add the important caveat that in 2023 we have a new government, following general elections in February and early March, and the current fiscal policy of the government could change. This is another instance, quite likely, where it will pay to keep abreast of the news in 2023.

Our overall view is then supplemented with data on redemptions, namely the incoming flows to the financial system that occur as T-bills (which, by definition, always mature within a year) and FGN bonds come due.

The current period is one where a high level of FGN bond redemption is expected and therefore we would reasonably expect, as a short-term effect (i.e. it may take effect over a period of a couple of weeks) market interest rates to come under downward pressure as we go into early May.

By way of caution, we need to add that CRR debits could also strongly influence liquidity during this period.

Beyond this, one would be advised to look for other drivers of short-term liquidity. Suffice it to say, there have been three occasions (in early-to-mid January, late March, and April) when it made good sense to lock in 1-year T-bill rates or deposit rates for 90 days (or 180 days) and other periods (late January, February and early March) when to do so was unwise.

Short-term rates – conclusion

What do we conclude from the above? How should we manage short-term Naira liquidity going forward? The key point, in our view, is to target a rate thatone deems to be acceptable and not to deviate from it on the downside.

A double-digit interest rate, in either 1-year T-bills or short-term deposits, seems to be a reasonable target, given that period of high liquidity has(e.g. during February) driven returns to below 5.0% annualised.

One could be a little more ambitious than this, perhaps, and target 12.0% annualised.

This, of course, is neither a precise nor an ambitious target, but a rule-of-thumb that would have worked well during the first four months of the year. Unless there is an overall rise in Naira-denominated market interest rates from the beginning of May onwards, this rule of thumb may work well over the coming months.

A few months is about as far as one can project forwards, given the changing nature of policy and the fact that ministerial appointments in the new government may signal a change in fiscal direction fairly soon.

Can we discount an overall rise in market interest rates going forward? We cannot, and in fact is it our base case for the full year 2023. As above, our overall argument for 2023 is that government borrowing is likely to have the effect of pushing market interest rates upwards. The issue here is how short-term liquidity drivers are going to influence short-term rates over the coming months.

The last trading days of April saw a large redemption of FGN bonds, creating system-wide liquidity, but the timetable of T-bill and FGN bond redemptions is sparse going forward. Conditions of tight liquidity may well return and it may be possible to shift one’s target benchmark upwards. An ambitious investor might work with a 14.0% target.

Of course, none of these yields are actually very exciting, since none of them exceed the rate of inflation which stood at 22.04% year-on-year in March. It is a matter of making the most of what is on offer.

Though this may seem a pessimistic judgment, it is important to recall that: a) Nigerian money managers last received a risk-free (i.e. government-issued) return above the rate of inflation in 2019, and b) things have actually been getting better since the dark days (alternatively, the liquidity-infested days) of 2020. We expect this trend to continue.

FGN bond rates

For all the ups and downs in the short-term money markets, the signs from the FGN bond market are that rates are indeed trending upwards, with the average yield-to-maturity of FGN bonds rising by just over one percentage point during the first four months of this year.

A low level of T-bill and FGN bond redemption combined with what we believe will be quite a high level of T-bill and FGN bond issuance may well continue to see FGN bond rates rise.

A feature of this trend is that the Naira risk-free yield curve has resumed its familiar shape, with a gentle slope from left to right, indicating a small premium available for holding long-term bonds. While this is not the place to debate the meaning of a gentle yield curve our point is that there has been a profound change since 2020 and 2021.

Anyone who was active in Naira fixed income markets for several years prior to 2019 will agree that this was the shape of the yield curve for many

years.

This is not to say that normal (i.e. pre-2019) money market conditions have returned: far from it.

The collapse of the domestic Open Market Operation (OMO) market (in late 2019), the large-scale (though not total) withdrawal of foreign investors from Naira-denominated fixed income markets, changes in the foreign exchange regime, the loan-to-deposit (LDR) policy applied to banks (during 2020) and, above all, the increase in the CRR has changed the market in ways that will be difficult to reverse.

The appearance of normality is deceptive. The market is taking shape every day.

Twitter-@theGBJournal|Facebook-the Government and Business Journal|email:gbj@govbusinessjournal.ng| govandbusinessj@gmail.com