This piece looks at Nigeria’s debt challenges over the medium-term with some reference to Belize and Jamaica, as well as a number of African credits.

”The key point is that I’m very wary of using debt/GDP comparisons – for reasons outlined in 2022 (see the Appendix) – and that debt/revenue ratios warrant concern,” Says Charlie Robertson Author of The Time Travelling Economist @TTTEconomist Global chief economist, Renaissance Capital

”This is most obvious in the domestic debt ratios – particularly if we take seriously the constitutionally important point that debt is issued by the federal government and it is responsible for finding the revenues to service that debt. The IMF is saying interest payments in 2027 will be 124% of federal revenues!’

MON. 20 MARCH 2023-theGBJournal | One of the fascinating things about Nigeria is that every data point is up for debate, except for its geographic size. How many people live in Nigeria? What’s the GDP of Nigeria? What’s oil output? What’s the naira worth?

When analysing default risk, the most important of these questions is the GDP debate, because we’re used to making international comparisons of debt (and other metrics) to GDP. Nigeria’s DMO points out the debt ratio of 26% of GDP in 2021 compares to a 60% benchmark for DM or 50% for EM. This is a healthy ratio.

Based on official revenue and GDP figures, it should be very easy for Nigeria to double government revenues from one of the lowest in the world at just 7% of GDP (similar to Somalia which also has uncertain population and GDP figures) to 14% of GDP. This would surely remove any risk of default.

But because the doubling of GDP in the 2014 update was not done in every country, there’s a decent case to make that we should not make % of GDP comparisons with other countries. It’s possible that debt/GDP is already 67% (using IMF debt figures and alternative GDP figures) and revenues are already 13% of GDP, close to the 17% SSA average in 2021. Looking at debt to revenue ratios tell us that Nigeria does carry default risk – a point supported by the recent downgrade to Caa1.

The February 2023 IMF Article IV has got more optimistic on the interest outlook relative to the October 2022 Outlook. The interest payments to federal revenues ratio is still large. By 2027, interest payments are forecast to be 124% of federal revenues; Sri Lanka peaked at 72% in 2021. Using the interest to general government revenues ratio (28% in 2022), it looks better than Sri Lanka, Egypt, Pakistan or Ghana and similar to Zambia, but it is unconstitutional for the federal government to take these revenues to pay debt.

The problem is on the domestic debt side, rather than the external side. Only a fifth of interest payments last year went to external creditors (equivalent to 5% of overall revenues). This is similar to Jamaica in 2010.

Nigeria has three choices and one dream scenario:

Inflate away domestic debt and repress market interest rates – a policy which has arguably been underway for some years. Very negative for the currency and that pushes up the external debt ratios, but assuming the fuel subsidy is removed and there’s a big devaluation, we’ll see a boost in oil-related tax revenues which compensates for this. Negative for the poorest in society due to inflation and for business investment due to inflation and FX volatility.

Restructure domestic debt. This is more common than external debt restructuring and tends to be quicker – it could be completed in 2023. This can bankrupt the banking sector. Bankruptcy of some banks might be tempered by regulatory forbearance.

Hike taxes and slash spending. Jamaica did similar. Unpopular and tough for any government, but especially one without a strong mandate (eg Pakistan today). Cuts inflation in medium-term, helps the currency and improves the credit rating.

In the dream scenario, oil leaps to $100-150/bbl and oil output rises to 2.5mbpd.

The interest/revenues problem is obviously a combination of two issues – interest and revenues but it is clouded by the dispute over GDP figures in Nigeria.

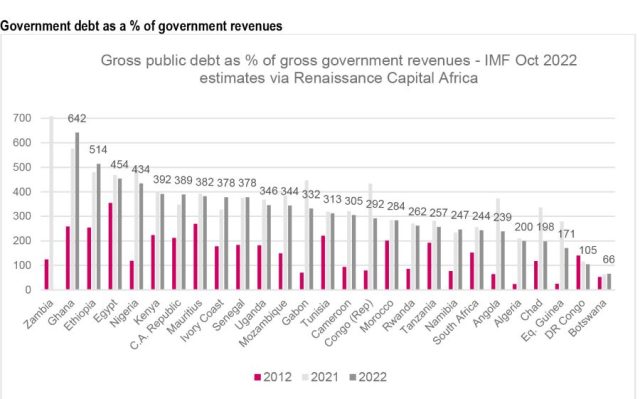

As an example of how ratios differ when we ignore GDP, see the ratio below which is government debt to revenues. Nigeria ranks 5th highest for debt risk, behind three countries already in the Common Framework for debt restructuring and Egypt.

The DMO 2021 annual report highlights that the public debt ratio was only 26% of GDP in 2021 – well below the 60% benchmark for advanced economies or 50% for EM. IMF estimates put it at 37% of GDP as they include overdrafts with the Central Bank of Nigeria. Using the IMF data, Nigeria ranks as the third least risky country in African credits we cover.

If the analysis in our Appendix is right though, then Nigeria’s ratio could be 67% of GDP, above the DM benchmark cited by the DMO. Using the official GDP figures makes it appear relatively easy for Nigeria to resolve the revenue problem – by doubling taxes – Nigeria’s revenues to GDP would jump from 7% to 14%, which would be close to the average SSA tax burden (revenues at 17% of GDP in 2021). But if the Appendix estimate for GDP is correct, then government revenues are already 13% of GDP. There is room for more revenues from a wider tax base, and a 4% of GDP increase to the SSA average would remove most of the headline budget deficit and stop the debt situation deteriorating. But it would not be easy.

Below we focus is on the interest / revenue ratio. Note the graph below has 3 figures for Nigeria – on the far right are the latest IMF estimates of interest payments to federal govt revenues from Feb 23. Just to the left of that is the estimates for interest to all revenues in Feb 23. And to the left of that is interest to all government revenues, estimated in Oct 2022 (worse ratios than the latest Feb 23 figures).

Where is the interest problem?

Domestic interest payments (21-25% of all revenues in the DMO forecasts for 2024-26) are the problem not external interest payments (5-6% of all revenues over 2021-26).

Note the DMO has benign forecasts for revenues and expenditure over the five-year period. While nominal GDP is estimated to rise 9-10% in 2023 and 2024, they see revenues rising 20% in 2023 and 3% in 2024, while total expenditure rises 8% and 7%, respectively. Revenue growth beats expenditure growth in every year except 2024.

The IMF Feb 23 estimates incorporate different GDP and inflation forecasts, but the key point is they expect expenditure to rise more than revenues in 2024, 2025 and 2026.

The main point is domestic debt appears to be the problem – not external debt. The external debt service to exports ratio is very good for Nigeria.

SOLUTIONS

– Inflate away domestic debt. Push inflation up to 60-100%, devalue the naira by 50% to our REER estimate of NGN670-680/$ or more, and end the fuel subsidy.

If nominal expenditure rose 0% in 2024, and oil revenues rose 50%, Nigeria could run a primary surplus in 2024.

Over half of Nigeria’s domestic debt with interest rates of 10-20% would mature with principal payments becoming very cheap to pay off relative to the amount that was raised originally, and under half would need to be rolled over at high interest rates (to reflect the high inflation).

Yes, the external debt ratio would then look worse – and repayment of external principal would be more expensive in NGN terms, but that’s relatively hedged by Nigeria’s oil revenues.

-Domestic debt restructuring. These are pretty common relative to external debt restructurings, and usually quick- sometimes just a month or two. Force the banks (and potentially mutual funds, pension funds) into a debt exchange. The problem is that the banks are often bankrupted via this process, but that can be covered up with regulatory forbearance (potential hits to capital ratios via provisions for foregone income, as well as possibly higher risk weights on government securities). This is however very disruptive, and like option 1, far from ideal.

-Massively increase taxes particularly on consumption (alcohol, cigarettes, fuel and perhaps VAT) and cut spending that fuels consumption (eg the fuel subsidy) – and with a combined 6% of GDP fiscal tightening, Nigeria could run a primary surplus, while supporting a shift from consumption to investment that should improve the current account and help lower interest rates. Politically difficult unless a leader has a very strong mandate.

– Pray for oil to be $100-150 and oil production to rise to 2.5mbpd.

– Nigeria’s GDP figures

One explanation for Nigeria’s low taxes is obviously that the country is under-taxed, but business people we’ve spoken to in Nigeria tell us tax collection tends to be very onerous and not far off DM levels. Another explanation is that GDP in Nigeria is overstated. If we look at government revenues in dollars, the revenue figures suggest Nigeria is the fifth biggest economy in Africa, not the biggest, while Kenya is the seventh largest, Tunisia is ninth and Ghana is tenth.

In 2021, Angola managed to collect $16-17bn (21-23% of its GDP) in revenues compared to $32bn (8% of its GDP) in Nigeria, despite its oil production averaging about 1.1mn bpd while Nigeria managed around 1.3mn bpd (US EIA data which appear to exclude gas condensates).

Oil was responsible for e.g. $9.6bn of revenues in Angola (implied from revenue ratios as per Table 1 of this January 2022 IMF report but updated with April 2022 IMF GDP estimates) and $13.8bn in Nigeria (implied from 3% of GDP in oil and gas revenues as per Table 1 in this February 2022 IMF report but updated with the latest April 2022 IMF GDP estimates).

This implies Angola collected $6.1bn from its people while Nigeria collected $19.7bn or 3.2 times more. But Nigeria’s population is 6.6 times larger, so in 2021, Nigeria only collected 5% of GDP in revenues from the non-oil sector while Angola collected 12% of GDP, which either means:

-there is far more poverty in Nigeria than in Angola – hence the lower revenue collection – but fertility and child mortality data suggest poverty levels are similar, or…

-Nigeria is spectacularly bad at collecting tax revenues and on a par with a failed state such as Somalia or war-like Yemen, but I don’t see a qualitive difference between Nigeria’s finance ministry and others I’ve been to, or…

– Nigeria’s population is much smaller than we think, but our 2019 estimates argued IMF and UN and Nigeria estimates are accurate and do make sense, or…

– non-oil GDP is smaller, by roughly that 3.2-to-6.6 ratio noted above, or around 48% the size that is officially recorded, implying Nigeria does not have the largest GDP in Africa, or…

– everyone else’s GDP is failing to account for the informal sector as well as Nigeria does, so we should double everyone else’s GDP, again implying Nigeria does not have the largest GDP in Africa.

If the right answer is that Nigeria’s non-oil GDP should be roughly halved, this would imply Nigeria’s total GDP is about $245bn instead of the $442bn that the IMF reports, and would make Nigeria the third-largest economy in Africa behind SA ($418bn) and Egypt ($403bn) but well ahead of Algeria ($165bn) and Morocco ($131bn). By comparison, five of the East

African Community members of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and DR Congo would together amount to about $291bn in 2021.

Government revenues then would be about 14% of GDP in 2021, similar to DR Congo, Côte d’Ivoire or Indonesia, and above Bangladesh or Sri Lanka, instead of 8% of GDP like Yemen or Somalia. From 2005 until the GDP revision in 2014, when oil prices were relatively high,

Nigeria revenues were above DR Congo or Pakistan in most years. Government debt would amount to 67% of GDP instead of 37% of GDP.

Gross external debt of $75bn in 2021 would amount to a still manageable 31% of GDP instead of 16% of GDP.

Per capita GDP would be $1,158 in 2021 (similar to Tanzania, Zambia or Uganda) – with Nigeria up at this level thanks to oil and despite lower adult literacy – instead of $2,089 (similar to industrialising India, Bangladesh or Uzbekistan).

Nigeria would not have the third smallest ratio of debt among Africa economies we cover, but would be mid-ranking, which would be concerning were oil prices to fall.

As a final aside – even within Renaissance Capital Africa– we have disagreement on this issue. Our SSA economist Yvonne Mhango points out that the previous rebasing of Nigeria’s economy before 2014 was in the 1990s. A big rise in GDP was to be expected in 2014. If we look at tax collection in Nigeria, an International Survey on Revenue Administration (ISORA) suggested less than 1% of adults (761,057 people) were paying income tax in 2016, this compares to about 3mn in Pakistan – where revenue collection is 13% of GDP. It is possible that much of Nigeria’s tax structure remains overly reliant on energy exports, even though energy exports per capita have dropped by some 75% over the past 40 years, and government revenue collection really is very low.

Twitter-@theGBJournal|Facebook-the Government and Business Journal|email:gbj@govbusinessjournal.ng|govandbusinessj@gmail.com