…How do we measure fair value? There are many ways, but here we focus on just one, the inflation differential

TUE MAY 14 2024-theGBJournal|Currencies do not trade at their fair value. Currencies may be cheap relative to other currencies for long periods of time and, conversely, they may be expensive for long periods of time, but it is supply and demand in the market that sets exchange rates, rather than fair value.

The fair value argument is that, if a nation’s currency is cheap relative to another country’s currency, then money will flow from the expensive currency to the cheap one in search of goods, services and investment.

That flow of money needs to buy the cheaper currency and therefore will balance the two exchange rates.

How do we measure fair value? There are many ways, but here we focus on just one, the inflation differential. The logic is as follows. A basket of goods and services in country X (say, the United States) once cost roughly the same, given the market exchange rate of the day, as in country Y (say, Nigeria).

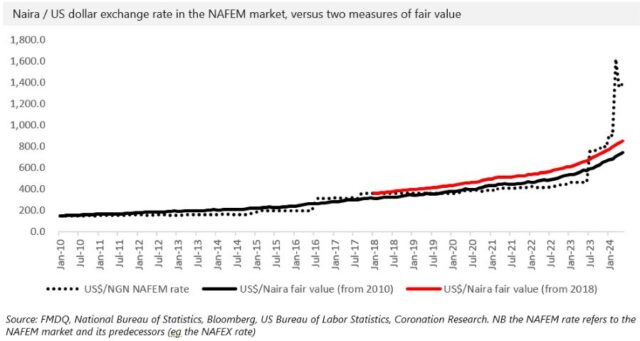

Subsequently US dollar inflation was low while Nigerian inflation was high, but the exchange rate did not change much (for example, between the years from 2010 to 2014).

The basket of goods and services Nigeria then cost a lot more in Nigeria than in the US, so the exchange rate needed to adjust.

The inflation-differential method is far-from-perfect, but in our view it has a compelling logic and can be cross-referenced with plentiful data (inflation). We know that currencies trade away from their fair values for long periods but we expect them revert to their fair values when cross-border trade and investment flows are working efficiently.

For much of the time our simple model works well. For example, the fair value during much of the period from 2010 to 2016 suggested a weaker exchange rate than the prevailing NAFEM rate.

Then, in 2016 and 2017, the exchange rate adjusted back towards to fair value (with several upheavals over those two years), as if brought to its senses by market forces.

One problem with this method is that it has a starting point, namely January 2010, using the market exchange rate at that time. But the exchange rate in January 2010 itself could have been overvalued (or undervalued).

So, we re-set the clock with another starting point, the exchange rate in January 2018, reasoning that the upheavals of 2017, which were followed by considerable inward investment, represent fair value. Using January 2010 and January 2018 as our two starting points gives a range of fair values today from N740.2/US$1 to N852.7/US$1.

It could be argued that a nation whose currency trades much below its fair value has lost a degree of confidence with its trade and investment partners.

Confidence is an intangible thing and measuring it is a specialised science. A year ago the exchange rate momentarily met with our two measures of fair value (see chart), but then weakened considerably more.

This suggests that a return of confidence has the potential to cause the Naira to appreciate considerably: the continued absence of confidence would simply mean prolonged Naira cheapness.

In the short term market forces will drive the exchange rate. As we have pointed out over the past few weeks, the clearing of all pent-up demand for US dollars and a degree of foreign portfolio investment would go a long way to resolving the Naira’s issues. In the background, at least one fair value measure suggests that the Naira is cheap.-Analysis is powered by Coronation Research

X-@theGBJournal|Facebook-the Government and Business Journal|email:gbj@govbusinessjournal.com|govandbusinessj@gmail.com